|

|

This topic comprises 2 pages: 1 2

|

|

Author

|

Topic: Variable Density Klang - Rashomon (1950)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Leo Enticknap

Film God

Posts: 7474

From: Loma Linda, CA

Registered: Jul 2000

|

posted 01-04-2016 03:02 PM

posted 01-04-2016 03:02 PM

Klangfilm was formed in 1928 as a consortium of Siemens and AEG, to produce technology to rival that of the pre-existing Tri-Ergon system (effectively, a recording system developed from the remnants of Lee de Forest's work in Berlin in the early '20s). Just as in the US, RKO was essentially RCA moving into the movie business to create a market for its audio products, so was Tobis (Tonbild-Syndikat) in Germany. Just as in the US, avoiding stepping on the toes of others' patents was a big part of what went on, especially in the immediate aftermath of the ERPI territorial divvy-up.

The Klangfilm side of the business diversified into broadcast technologies and non-film recording technologies, including some consumer audio products. Klangfilm became fully controlled by Siemens in 1941, as part of the Nazi government's drive to centralize control of communications technology production, and persisted as a brand/badge name well into the 1960s, as Mark points out.

However, and I'd have to go back to notes and reference material to confirm this definitively, their R & D on optical film sound recorders was effectively over by the late 1930s, and so as far as variable density optical mastering is concerned, Klangfilm is effectively a 1930s technology.

The conversion to sound in Japan's film industry happened significantly later than in most of the rest of the world, partly because the tradition of live performance (including mime and speech - not just music) alongside the projection of silent films became established, popular and persisted well into the 1930s. By the time Japanese theaters and studios were equipping for sound seriously, Japan's only well established trade links with a country that made and exported this technology were with Germany, hence my speculation that this is why Jane has a 1950 Japanese film with a Klangfilm track.

About 4-5 years ago, in Leeds, before moving to the US, I showed a print of a 1950s Japanese movie. I remember it for two reasons. 1 - it had absolutely the thinnest, noisiest and nastiest of any VD track I've ever played. It was a 35mm reversal print from another release print, which didn't help it, but the source track must have been very bad to start with. Even a fluent Japanese speaker in the audience told me that she wouldn't have been able to understand the dialog if it weren't for the English subtitles. 2 - until Son of Saul came out last year, it would have won my nomination for the most depressing movie ever made. It was called The Eternal Breasts, and its plot can be summarized in a single sentence: woman takes six reels to die in agony of breast cancer. I wonder if that track was mastered with 1930s Klangfilm sound cameras, too.

BTW, we're showing Rashomon later this month, on 35mm according to the info I have, along with several other Kurosawas. I'll be interested to see what the tracks are like on them.

| IP: Logged

|

|

|

|

|

|

Leo Enticknap

Film God

Posts: 7474

From: Loma Linda, CA

Registered: Jul 2000

|

posted 01-05-2016 11:53 AM

posted 01-05-2016 11:53 AM

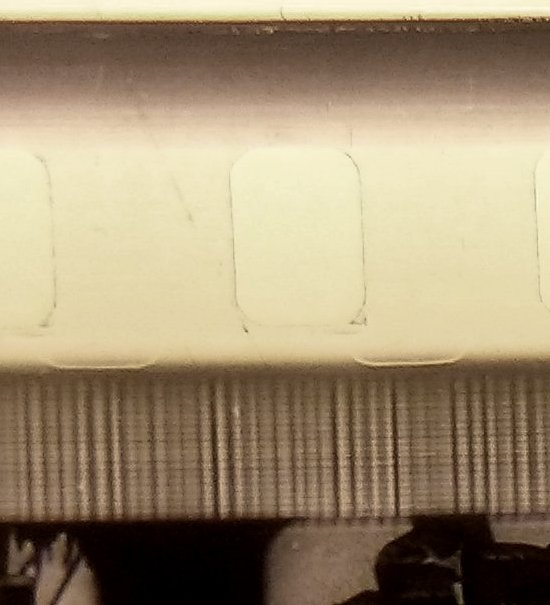

Thanks for the pic - interesting. Note the perforation edge images on the outboard edge of the track, between the perforations of the actual print stock. I'd guess that the track neg had already shrunk a bit by time this reprint was done 18 years after the movie was made, hence they didn't align with the perforations in the print stock entirely. It may be necessary to adjust the alignment of the photocell of the projectors playing this print, to avoid a "brrrrr" noise from being picked up.

quote: Bill Brandenstein

For the amateurs (like me) and otherwise uninitiated in this crowd, what differentiates a Klangfilm variable density track from any other...

Visually in terms of the modulation itself, nothing. Just as you can't see the difference between A-type and SR, the output of different VD sound cameras does not create a visual signature in the modulation. If you want to know which sound camera exposed the track neg from which your print was made, you need to look for other evidence, e.g. edge marking on the track neg stock (some stocks were made specifically for use in certain types of sound camera, e.g. the Kodak ultra-violet stock for RCA equipment), or writing on the leader that could tell you.

quote: Bill Brandenstein

Also, is this a type of recording we're likely ever to see in 16mm?

Unless you like collecting 16mm prints of Nazi entertainment films, unlikely but possible. In the days when 16mm prints of feature films were made in significant numbers (for TV broadcast, airline use, schools, universities, film societies, that sort of audience), a 16mm pic and track internegative was usually made first, and then the print(s) from that. Occasionally, for one-off prints of minority interest titles, a 16mm release print was optically printed on reversal stock straight from a 35mm release print, but you took a huge quality hit by doing that, especially in the loss of midrange and gamma. This was a very cheap, very low quality option.

For the optical audio, the 16mm track interneg was made either by optically printing a 35mm track neg onto 16mm stock, or by exposing a new 16mm track neg in a 16mm sound camera, from a magnetic tape of the film's mono final mix. 16mm VD sound cameras certainly did exist, but as with 35mm, declined in use from the late '50s onwards, when patents for VA technology started to expire and its use widened.

Re-recording a 16mm track neg gave you better sound, but was more expensive.

The problem with variable density is not that it was an inherently "worse" way of recording optical sound: it was that it needed much more critical quality control and was much less tolerant of minor slips than VA. In particular, sensitometry and densitometry in the lab had to be just right, because a slightly overexposed or underexposed (overly dense or overly light) track would affect the gain far more with VD than with VA. Loss of signal quality through successive generations of duping also tended to be worse with VD than with VA, which was obviously a major issue before the days of magnetic recording, when studio recording and post-production dubbing had to be done optically, too. A VD track can sound great, but throughout the recording, duplication and playback chain there are more factors that are likely to degrade it than with VA, as a general rule, which is essentially why the industry gradually abandoned it after the major patents on VA technology expired.

Jane - we're doing a major Kurosawa season at the end of this month, all on 35mm. The print of Seven Samurai is already in the booth, but I haven't looked at it yet because we have a limited number of house reels and it would be difficult for this print to occupy 10 of them for the next fortnight. I'll let everyone know what I find on the audio when the time comes, though.

| IP: Logged

|

|

Bill Brandenstein

Master Film Handler

Posts: 413

From: Santa Clarita, CA

Registered: Jul 2013

|

posted 01-05-2016 01:00 PM

posted 01-05-2016 01:00 PM

Thanks for the fantastic picture & explanations, friends. Jane, however you shot that photo is just wonderful. Look at the photo at full size, and yes, you see the placement and hole shadows as Leo noted, but something else I've never seen on a VA track: there are roughly 20 "lines" where the sound information is uneven across the width of the track - a rather inefficient way of "spreading" the modulated light seems to have been used. Seems like that would also lend itself to more distortion and noise... go figure.

Here's a pertinent anecdote to Leo's technical explanation above. I was kindly given some VS prints in 16mm a few years ago to play with, and one was a studio original of "Thanks a Million" from 1935 (printed on 1960 Kodak B&W). To look at the VA track is to see nothing unusual; in fact, it's not even particularly dark. However, to play it is to hear something special from that era: a frequency range (high and low) plus dynamic range that defies its age, and gives clear evidence of why the film won an Oscar for sound. Some mag-originated tracks don't sound as good as what Fox put out on this one.

| IP: Logged

|

|

|

|

|

|

Leo Enticknap

Film God

Posts: 7474

From: Loma Linda, CA

Registered: Jul 2000

|

posted 01-06-2016 11:07 AM

posted 01-06-2016 11:07 AM

I'd guess uneven film transport speed through the continuous contact printer, dirt on the slit, or another defect of that sort.

This is a 1968 print of a rep/rerelease title. The thing to remember about film printing in those days is that it was very variable in quality. Pretty much any film print made now will have received TLC from the lab and been made with the utmost care on scrupulously maintained equipment, just as any vinyl LP pressed now will be a 180 or 200-gram pressing on high grade PVC with no more than 25 minutes on a side. Both are almost obsolete media, and the only customers for them remaining are only interested in the highest quality those media can deliver.

That wasn't the case in the days of film as a mainstream release medium. There were showprints made at elite labs, which were amazing, and one-light dupes made at small, under-resourced labs where the printer film paths weren't kept properly clean, outdated stock bought cheaply was used, the chemistry wasn't replenished to spec, etc. etc.; just as in the 1970s you could buy a Sheffield Lab audiophile pressing, or (for about a fifth of the price) a Dynaflex record with 40 minutes on each side, on wafer-thin PVC with bits of recycled paper embedded in it, and so on.

quote: Jack Theakston

Well-processed new prints with tracks from the original negative often sound particularly good, even better compared to their year-of-release counterparts, I've often found. Universal often uses original track negs on their repertory prints, and the fidelity is, with few exceptions, very good.

For a typical feature film, contact printing the track neg shot in the studio straight onto the release print is not an option, because it won't incorporate mixes, dissolves, fades, EQ-ing and all the other processing that took place in post. If a final mix track interneg dating from the original release exists and has not decomposed or shrunk beyond the point of usability, then it would be preferable to an analog remastering, if, in the case of VD, it's possible to maintain the highest possible QC in the duplication process.

I played around a dozen Universal 35mm re-release prints at Cinecon last year, mainly prints of '30s and '40s shows made between the '80s and early '00s. The audio quality was extremely variable, ranging from lovely to barely acceptable. Most were twin bilateral VA re-recordings, but there were one or two VDs. Can't remember much about the VDs specifically, so am guessing that they were basically unremarkable.

| IP: Logged

|

|

|

|

Simon Wyss

Film Handler

Posts: 80

From: Basel, BS, Switzerland

Registered: Apr 2011

|

posted 01-07-2016 01:34 PM

posted 01-07-2016 01:34 PM

Hello, Jane

Sven Berglund invented the multi-track variable-area recording, over the nomimal .999" space between the hole rows. It was him who performed the world’s first public presentation of synchronous sound with pictures on February 17th, 1921 in Stockholm. The system provided for twenty-two tracks. That number was later reduced to fourteen. Often less sharp MTVA recordings are mistaken as variable density tracks but upon close examination the difference can be seen. True VD tracks have homogenous lines.

The Triergon patents date from 1919. 20 years were the run time of a Reichspatent. The latest patent on VD recording elapsed in 1943.

Leo Enticknap is certainly right with the presumption that German equipment can have found its way to Japan although I tend to upkeep some scepticism here. We do not know better at this time.

Of the TOBIS-Klangfilm union TOBIS took over the manufacture of sound cameras and the Klangfilm trust engaged in fabricating projector equipment plus their sale. The contract was closed on March 13, 1929. UFA joined at that point, too.

The out-of-alignment printed perforation holes from the sound negative as you are showing us can derive from a non-slip printer. These came into use in the second half of the 1930s. TOBIS-Ag. built one and the Bell & Howell Co. built one. On a non-slip sound printer the strict relation between primary film and raw stock no longer exists, that is why the perforations are unlocked.

Since I know some about lab techniques I have invented a duplicating process for photographic sound tracks on heavily shrunk film, named Orthopos, by which the shrinkage can be set aside without any mechanical or optical or electrical interference. It is pure reprography.

| IP: Logged

|

|

|

|

|

|

All times are Central (GMT -6:00)

|

This topic comprises 2 pages: 1 2

|

Powered by Infopop Corporation

UBB.classicTM

6.3.1.2

The Film-Tech Forums are designed for various members related to the cinema industry to express their opinions, viewpoints and testimonials on various products, services and events based upon speculation, personal knowledge and factual information through use, therefore all views represented here allow no liability upon the publishers of this web site and the owners of said views assume no liability for any ill will resulting from these postings. The posts made here are for educational as well as entertainment purposes and as such anyone viewing this portion of the website must accept these views as statements of the author of that opinion

and agrees to release the authors from any and all liability.

|

Home

Home

Products

Products

Store

Store

Forum

Forum

Warehouse

Warehouse

Contact Us

Contact Us

Printer-friendly view of this topic

Printer-friendly view of this topic