|

|

|

|

Author

|

Topic: Italian cinematographer Tonino Delli Colli dies

|

Tim Reed

Better Projection Pays

Posts: 5246

From: Northampton, PA

Registered: Sep 1999

|

posted 08-20-2005 02:26 AM

posted 08-20-2005 02:26 AM

Tonino Delli Colli has died at 82. He lensed such well-known works as "The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly", "Once Upon a Time in the West", and "Life is Beautiful", among many others.

Hollywood Reporter

ROME -- Legendary cinematographer Tonino Delli Colli, who worked alongside many of Italy's film titans over the past six decades, died at his home in Rome on Wednesday. He was 82. Working with such storied directors as Federico Fellini, Pier Paolo Pasolini, Sergio Leone, Roman Polanski and Roberto Benigni, Delli Colli amassed an impressive filmography. Among the more than 130 films Delli Colli worked on were Leone's "Once Upon a Time in the West," Pasolini's "The Canterbury Tales," Fellini's "Ginger and Fred," Polanski's "Death and the Maiden," J. Jacques Annaud's "The Name of the Rose" and Benigni's "Life Is Beautiful," the cinematographer's final film. (Peter Kiefer)

| IP: Logged

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

John Pytlak

Film God

Posts: 9987

From: Rochester, NY 14650-1922

Registered: Jan 2000

|

posted 08-26-2005 09:10 AM

posted 08-26-2005 09:10 AM

RIP. ![[Frown]](frown.gif)

http://www.kodak.com/US/en/motion/newsletters/onFilmInterviews/delli.jhtml?id=0.1.4.9.6&lc=en

quote:

Tonino Delli Colli, AIC

"I never went to film school or read any books about film. It was a natural instinct... an intuition. I can't explain it because it's not a tangible thing. It's just a part of me. Neo-realism was born during the years following World War II, when there wasn't a lot of money available. The defining characteristic of those films was that they were shot in real-life environments. We only used ambient light and the light coming through windows as the starting point for photography. I've never used preconceived formulas. I've always worked with the human and technical resources available, and used my imagination and intuition. If anyone asks me about my films and about how I created them technically, I always tell them to go to the theatre and watch them again because everything is right there. The magic of film can't be put into words."

Tonino Delli Colli, AIC received the American Society of Cinematographers International Achievement Award in recognition of his enduring contributions to the art of filmmaking in 2005. He photographed 137 motion pictures between 1944 and 1997, including including Ginger and Fred, Fellini's Intervista, The Voice of the Moon, Bitter Moon, Death and the Maiden, The Name of the Rose, Tales of Ordinary Madness, The Gospel According to St. Matthew, The Canterbury Tales, Once Upon A Time in the West, Once Upon a Time in America, The Good, The Bad and the Ugly and Life Is Beautiful.

Published in American Cinematographer / March 2005

A Lifetime Through the Lens: Tonino Delli Colli, AIC

by David Heuring and Giosue Gallotti

Tonino Delli Colli, AIC, went to work at Cinecittà, the Italian film studio, in 1938, barely a year after it opened. Delli Colli himself was all of 16 years old. Asked where he wanted to work, in the sound department or with the cameramen, he said "With the cameramen."

"Life is always a matter of luck," says Delli Colli. "At the time I had no idea what being a cameraman meant, or that those few words would determine the course of my life. Sometimes just a word or two can change everything."

Sixty-seven years later, Delli Colli's life and work was honored by the ASC, an organization that was almost 20 years old when he began his career. Delli Colli received the ASC International Achievement Award, joining such giants of world cinema as Freddie Young, BSC, Jack Cardiff, BSC, Gabriel Figueroa, AMC, Henri Alekan, Raoul Coutard, Freddie Francis, BSC, Giuseppe Rotunno, ASC, AIC, Oswald Morris, BSC, Billy Williams, BSC, Douglas Slocombe, BSC, Witold Sobocinski, PSC and Miroslav Ondricek, ASC, ACK.

"What astounds me about Tonino's career is not only its duration, spanning six decades from the late 1940s to the early '90s, but the amazingly eclectic breadth of his work," says John Bailey, ASC. "He worked with an amazing number of auteur directors, including Pier Paolo Pasolini, Federico Fellini, Roman Polanski, Jean-Jacques Annaud, Claude Chabrol, and, of course, Sergio Leone. The titles alone mark the diverse nature of his work: Lacombe Lucien, Intervista, Bitter Moon, The Good, the Bad and the Ugly, Accattone, The Name of the Rose and Life is Beautiful.

"It is his very resistance to thematic or stylistic predictability that has always fascinated me about his work," says Bailey. "He adapts himself to the director and the dictates of the scenario rather than forging a consistent, signature style. This diversity is a goal that I have striven for in my own work. He has been a beacon for me and for many others."

Delli Colli took his first steps towards greatness under the watchful eyes of such master cinematographers as Mario Albertelli. "For a long time I served as an apprentice - something that doesn't exist anymore," says Delli Colli. "Craftsmanship has disappeared along with it. When students graduate from some film schools they might call themselves 'cinematographers,' but what does that mean? These clever young fellows 'earn their spurs' with one of us.

"Fortunately, I grew up professionally with a fine cinematographer," he says. "I worked with him for about three years, and he was like a father to me. I never went to film school, I never read any books about film, and I never knew what went on in the development bath or during the printing process. I learned this trade 'hands on,' watching what the professionals of the era were doing and valuing the advice they gave me. That was all I needed, because in the projection room I was able to grasp all of the mistakes that were made during shooting or development, and/or the flaws caused by the resources that were used - the cameras, the film, etc. It was a natural instinct - an intuition. I can't explain it, because it's not a tangible thing. It's just a part of me."

When Albertelli fell ill, Delli Colli took on more responsibility. "Albertelli was suffering from an ulcer, and often he let me do what I wanted," Delli Colli recalls. "He gave the instructions, and I did the preparatory work and went forward with it. He shot the scenes and made the corrections. That's how you learn how to do things. I wasn't the boss, but I could still create the images. However, I can't deny that at a certain point I was upset when he came and changed things."

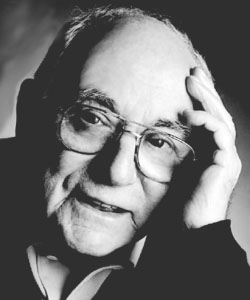

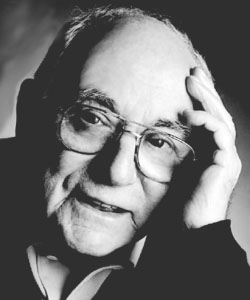

Tonino Delli Colli, AIC

(photo by Douglas Kirkland)

Delli Colli continued his emergence as an artist by making films with directors Carlo Ludovico Bragaglia and Mario Bonnard. After the war, he honed his operating skills by working with master cinematographers Ubaldo Arata and Anchise Brizzi. "I made so many films I can't remember them all," he says.

The postwar period saw the flowering of what is now known as Italian neorealism. Delli Colli was at the heart of this movement, which had a strong influence on world cinema and is cited as inspiration by such Hollywood directors as Martin Scorsese and Brian De Palma. The realism was born in part because money was short and filmmakers had to make do with what was at hand. Real locations were used instead of sets and stages, and lighting was often done with the sun or natural ambient sources.

"Black-and-white was the type of film that best represented these types of stories," says Delli Colli. "The photography was very different from what is done today. I really liked working with black-and-white, and I have to say that, in comparison with color, we got better results and more satisfaction from our work.

"Neorealism is a completely Italian thing," he says. "The defining characteristic of these films, which later gave their name to this particular period, was that they were shot in a 'real-life' environment. That is, there were no ceilings or superstructures that would have helped light the scene or even out the lighting for the entire setting. We could use only the ambient light or the light that was coming through the windows, and that was the starting point for the photography. Cinecittà was full of displaced persons. The neorealistic stories were all dramatic, unhappy stories of postwar life."

In the 1950s, Delli Colli made a contractual commitment with Carlo Ponti and Dino De Laurentiis to make five films a year. He worked on every kind of film, including comedies, formula stories and "Toto" films. Toto was a popular Italian comic genius who worked in theater, film and television. It was on a Toto film that Delli Colli first worked in color. The project was Steno's Totò a colori (Toto in Color). The story concerned a musician, Antonio Scannagatti (Totò), who hopes to sell his composition to one of the most important Italian impresarios. The film, the first Italian color film, used a monopack color process developed by a company called Ferrania. The ASA of the film was six.

"No one else wanted to do it," Delli Colli says. "They chose me, saying 'You're under contract so you'll do what we tell you.' All we had available was the lights for shooting with black-and-white film, because color lamps didn't exist yet. The lighting became extremely complicated. I said 'Are you all crazy?' In short, what they wanted was an avalanche of light. And poor Toto was subjected to these showers of light. Poor little guy. Among other things, he was already prone to eye problems. As soon as Steno, the director, called 'Stop,' Toto was off. He wanted to get out of that inferno as soon as he could."

Delli Colli notes that the arrival of color changed every aspect of the cinematographer's job: the film, the exposure, the lamps, the lab equipment, processing, etc. "Like everyone else, I had to study the new product, with help from Kodak and from the laboratories," he says. "I got furious with Kodak whenever a new negative came out because I had always wanted to use the same film. With each new product I had to start again from scratch.

"The shooting technique was more or less the same," he says. "There was a substantial change in the concept of things that had originally been considered secondary ? such as set design, set decoration, and costumes. Everything took on a different importance and a different value. There's no question that cinema has gained something through the advent of color, but I also think it has lost a lot. Black-and-white made it possible to create unique and irreproducible atmospheres."

In 1961, Delli Colli was in Africa working on an American production called The Wonders of Aladdin. "Flavio Mogherini, an architect on the production, told me that he had been contacted by Alfredo Bini for a new project directed by Pasolini," he recalls. "I told him I would be happy to work with a new director, and asked him to mention my name to Bini. Mogherini said I was too expensive, so I asked them to tell Bini to give me whatever he could. I believe that was fate because that day completely changed my career.

"It wasn't hard, though. Pasolini was smart enough to ask me what to do," Delli Colli continues. "What he had in mind was something intangible but very clear. He gave me specific suggestions, and I implemented them. With color, however, he became more analytical, because he had pictorial references, such as the painting by Mantegna that he used in La Ricotta (The Curd Cheese). He tried to work with the costumes, selecting the colors. Over time, Pasolini assembled a great group of artists, including Dante Ferretti and Danilo Donati."

Pasolini and Delli Colli collaborated for the next 15 years, making landmarks of world cinema like Accattone, Salo o le 120 giornate di Sodoma (Salò or The 120 Days of Sodom), The Canterbury Tales, Hawks and Sparrows and Decameron. These were visually radical films even by the rule-breaking standards of the New Wave.

Delli Colli photographed 11 of Pasolini's 14 films, and only scheduling conflicts prevented him from shooting them all. In 1964, they made Gospel According to St. Matthew. That film earned the cinematographer his first prize, a Silver Ribbon, the first of seven.

"Pasolini was something else," says Delli Colli. "Our relations were perfect. He was an incredibly sweet and kind person, and he had respect for everyone on the set. I knew he was good, even if, at the start, he didn't have a technical knowledge of cinematography. When we started our first film (Accattone) together, I had to explain to him what lenses were. But after three weeks, and I do mean three weeks, he understood it all.

"He was happy right away with the 50 [mm lenses], because the performers could be seen clearly, even though the backgrounds were closer and were a little squashed. But he said that was all right with him, because everything was more concentrated. Ultimately, he came to the set in the morning with his apertures, which were fairly poorly specified but which were the right ones, and he worked quickly. He had planned everything and laid it out the night before, knowing whether he wanted a full shot or something else. He did that for the first two films. Then things took off from there."

In the 1960s, Delli Colli also began his working relationship with Sergio Leone, which would bring him his greatest fame in the United States. Leone and Delli Colli re-imagined the Westerns of John Ford and Howard Hawks, taking genre films to the level of art through glacial but tense pacing; innovative sound design; fresh, minimalist dialog and above all, obsessive and almost exclusive use of extreme close-ups and very wide vista shots.

The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1966) was reportedly made for $250,000 and was a blockbuster hit. Once Upon a Time in the West (1968) used a bigger budget, with Henry Fonda cast against type as a ruthless villain.

"Sergio was a skinny kid who was working as an assistant to Bonnard," Delli Colli recalls. "After Bonnard died, Sergio finished the shooting of The Last Days of Pompeii, and then directed The Colossus of Rhodes. Sergio came to Spain where I was making a [Luis García] Berlanga film called El Verdugo (The Executioner, also known as Not on Your Life) with Nino Manfredi. It was 1963, and he was looking for money from our producer, the former goalie of the Real Madrid who in turn was being financed by a pharmaceutical company. He had the idea of making a film about the eagles of Rome with the Romans and all the others. But there wasn't a cent to be had.

"Back in Rome, one night he took me to see Kurosawa's Yojimbo. He told me it was a good idea for a low-budget Western. That was true because all the action took place in one little town. And little towns like that were still around in Spain. So I helped him find the producer, but I had no plans to make the film myself because I couldn't work for nothing."

Later, Delli Colli heard that in Rome there were near riots at the Supercinema with SWAT teams outside the theater. The crowds were trying to get in to see A Fistful of Dollars, an surprise international hit that kick-started Leone's career.

"Sergio was a real go-getter, a very meticulous artist who paid attention to everything he did right down to the smallest details," says Delli Colli. "For the images, he asked for things that were truly effective - full light for the long shots because he wanted the details to be visible on screens of all sizes, and close-ups with the individual hairs of the characters' beards visible. It was impossible in Spain because of the heat. He wanted deep, long shadows ? the deepest and longest that we could get. And the light came down late. On the set, we prepared in the morning and then we just died waiting for the right light. I did everything I could, within the limits of what was possible to accommodate him. And then there were the details. He wanted to shoot the eyes in every scene. I told him we could shoot 100 meters of eyes - looking here, looking there - and then use them whenever he wanted. But he wasn't having any of that. And that's how it went for the entire shoot. But his three-hour films pass quickly. A three-hour film made today is a chore to sit through."

Delli Colli's collaboration with Leone reached its apogee with the masterpiece Once Upon a Time in America, a sweeping gangster epic that was butchered in the editing room prior to its release in America. The restored version, with Leone's original out-of-sequence editing, has only been seen in the United States relatively recently.

"Once Upon a Time in America was a long film because there were a lot of interruptions, because of Sergio's meticulousness and his desire to make a film that would be unique in its genre," says Delli Colli. "First we couldn't find the right actors because he had certain specific types in mind, but we kept looking. Even though he couldn't speak a single word of English he was able to make himself understood by using French, always with a smile on his lips. And the American actors loved working with him. The interiors were shot in Rome, at the De Paolis Studios, and the exteriors were shot in the Puerto Rican neighborhood in New York. It was the sets themselves that inspired my choices in terms of the cinematography. The story of the film was a complex one, but when you see it you understand that it was worth the trouble. It displays all of Sergio Leone's artistry."

Delli Colli made four films with Federico Fellini, including The Voice of the Moon (1990), Intervista (1987) and Ginger and Fred (1986). "Fellini was fairly easy to work with ? you just had to get to know him a little," he says. "He had the habit of often changing things at the last minute. But I was aware of that, and so I always had with me everything I needed to deal with his 'improvisations.' Fellini never worked with notes or a script. He invented everything on the spot. Federico was very specific in terms of cinematography on a shot-by-shot basis. For The Voice of the Moon we did everything in the dark of night, which called for a lot of inventiveness. For example, for the scene with the fireflies, I had tiny lamps made that we suspended from fishing rods, dancing in front of the camera. Fellini had been thinking about using real ones; he didn't know that they'd become extinct."

During his seventh decade of filmmaking, Delli Colli began a new collaboration, this time with Roberto Benigni on Life is Beautiful. "When I did Life is Beautiful, I was torn," says Delli Colli. "I initially wanted to use dramatic light but instead went with a more clear cinematography, more in the style of the classic comedies. Life is Beautiful is a comedy, even when it becomes dramatic. With Benigni, as with any comedian, the audience has to be able to see his face clearly."

Benigni won the Academy Award for Best Actor for his performance in the film, and Life is Beautiful won the Best Foreign Film Oscar. Nominations came for writing, directing and best picture.

Delli Colli has won seven Silver Ribbon awards, which are presented by the Italian National Syndicate of Film Journalists: in 1965 for Pasolini's Gospel According to St. Matthew; in 1968 for Marco Bellocchio's La Cina è vicina (China is Near); in 1982 for Marco Ferreri's Storie di ordinaria follia (Tales of Ordinary Madness); in 1985 for Once Upon a Time in America; in 1987 for The Name of the Rose; and in 1998 for Marianna Ucria. He has also won four David di Donatello awards, Italy's equivalent of the Academy Award: in 1982 for Tales of Ordinary Madness; in 1987 for The Name of the Rose; in 1997 for Marianna Ucria, and in 1998 for Life is Beautiful.

"In my work I've always tried to 'illuminate' the stories that are being told, using the simplicity of my feelings and the instinct that has guided me, that's a part of me, with no irritations or exasperations," says Deli Colli. "A better way to put it might be that I've never used 'preconceived formulas' to get a certain result. Instead, I've always worked with the human and technical material that was available, and with the imagination and intuition of the moment.

"One great actor whom I liked very much was Marcello Mastroianni. Like me, he played down his work and tried to demythologize it. Marcello always said that he was lucky because he had the best job in the world, and I share that thought with him. I've met great professionals who have allowed me to express myself as best I can through images. And if anyone asks me about my films, about how I created them technically, I always tell them to go to the theater and watch them again because everything is right there. The magic of film can't be put into words."

Extracts of the interview are taken from Silvio Danese's Anni fuggenti

© RCS Libri S.p.A., 2003, Bompiani

| IP: Logged

|

|

|

|

All times are Central (GMT -6:00)

|

|

Powered by Infopop Corporation

UBB.classicTM

6.3.1.2

The Film-Tech Forums are designed for various members related to the cinema industry to express their opinions, viewpoints and testimonials on various products, services and events based upon speculation, personal knowledge and factual information through use, therefore all views represented here allow no liability upon the publishers of this web site and the owners of said views assume no liability for any ill will resulting from these postings. The posts made here are for educational as well as entertainment purposes and as such anyone viewing this portion of the website must accept these views as statements of the author of that opinion

and agrees to release the authors from any and all liability.

|

Home

Home

Products

Products

Store

Store

Forum

Forum

Warehouse

Warehouse

Contact Us

Contact Us

Printer-friendly view of this topic

Printer-friendly view of this topic

![[thumbsup]](graemlins/thumbsup.gif)

![[Frown]](frown.gif)