|

|

This topic comprises 3 pages: 1 2 3

|

|

Author

|

Topic: Keeping Film Alive

|

Victor Liorentas

Jedi Master Film Handler

Posts: 800

From: london ontario canada

Registered: May 2009

|

posted 09-01-2017 03:21 PM

posted 09-01-2017 03:21 PM

http://www.newstatesman.com/culture/film/2017/08/can-celluloid-lovers-christopher-nolan-stop-digital-only-future-film

Can celluloid lovers like Christopher Nolan stop a digital-only future for film?

Despite proponents like the Dunkirk director, physical film is finding it tough in the modern age.

By Daniel Curtis

Sign up for our weekly email *

“Chris Nolan is one of the few producing and directing films right now who could open that film. He is one of the all-time great filmmakers.”

No prizes for guessing which new release Vue CEO Tim Richards is talking about. Aside from its box office success, aside from its filmmaking craft, aside even from its early reception as an Oscar favourite, Dunkirk sees Nolan doing what Nolan does best: he has used his latest film to reopen the debate about celluloid.

Until relatively recently all film was projected from that old, classic medium of the film reel - a spool of celluloid run in front of a projector bulb throwing images on to a screen. It comes mainly in two forms: 35mm (standard theatrical presentations) or 70mm (larger, more detailed presentations most popular in the 60s and 70s). Fans say it provides a “warmer” colour palette, with more depth and saturation than modern digital formats.

But now it’s hard to even see movies on film to make the comparison. After George Lucas, godfather of the Star Wars franchise, shot Star Wars Episode II: Attack of the Clones entirely in digital rather than on physical film, the rollout of digital progressed with clinical efficacy. Within ten years, film was almost wiped out, deemed to be impractical and irrelevant. Modern cinema, it was argued, could be stored in a hard drive.

Christopher Nolan set out to change all that. He championed film as a medium against the industry trend, producing (The Dark Knight, The Dark Knight Rises, Interstellar) in super-detailed, super-sized IMAX 70mm. With Dunkirk, Nolan has taken that further by screening the film in 35mm, 70mm and IMAX 70mm.

Nolan is not the medium's only poster boy – it is symbolic that the new Star Wars trilogy, 15 years on from Attack’s groundbreaking digital filming, is now being shot on film once more. This summer, Dunkirk may well be seeing the biggest rollout of a 70mm presentation in cinemas for 25 years, but in 2015 Quentin Tarantino’s The Hateful Eight saw chains and independent cinemas having to retrofit 21st Century cinemas for a 20th Century presentation style. It was a difficult process, with only a handful of screens able to show the film as Tarantino intended – but it was a start.

Today, celluloid is, ostensibly, looking healthier. A recent deal struck between Hollywood big wigs and Kodak has helped. Kodak will now supply celluloid to Twentieth Century Fox, Disney, Warner Bros., Universal, Paramount and Sony. It’s a deal which is not only helping keep Kodak afloat, but also film alive.

Kodak has also gone a step further, launching an app to help audiences find 35mm screenings in local cinemas. Called ‘Reel Film’, it endeavours to back Nolan and co in ensuring that celluloid is still a viable method of film projection in the 21st century.

Even so, whether Nolan’s film fightback has actually had any impact is unclear. Independent cinemas still screen in film, and certainly Vue and Odeon both have film projectors in some of their flagship screens, but digital dominates. Meanwhile, key creatives are pushing hard for a digital future: Peter Jackson, James Cameron and the creative teams at Marvel are all pioneering in digital fields. Whether or not film can survive after over a decade of effacement is a difficult – and surpisingly emotionally charged – question.

****

Paul Vickery, Head of Programming at the Prince Charles Cinema in London, is the kind of person you might expect to talk all about how physical film is a beautiful medium, key for preserving the history of cinema. History, he tells me, is important to the Prince Charles, but it's a surprise when he says film is actually more practical for their operation. Because not every film they screen has been digitised, access to old reels is essential for their business.

“If you completely remove film as an option for presentation as a cinema that shows older films,” he says, “you effectively cut 75 per cent of the films that you could possibly show out of your options, and you can only focus on those that have been digitised.”

Vickery says the debate around film and digital often neglects the practicality of film. “It's always focusing on the idea of the romance of seeing films on film, but as much as it is that, it's also to have more options, to present more films. You need to be able to show them from all formats.”

That’s a key part of what makes the Prince Charles Cinema special. Sitting in London's movie-premier hub Leicester Square, the Prince Charles is renowned for its celluloid presentations of older films and has made a successful business out of its 35mm and 70mm screenings of both classics and niche films. They're currently running the Check the Gate festival, which is, in their words "a celebration of films presented from film".

“If there is the option to show film and digital, we tend to take film as the option because it's also something you can't replicate at home,” he explains. “It's also just the nature of how film is seen on screen: its image clarity, its colour palette, the sound is just something that's very different to digital, and I think that's something that's very worth saving.

“Not many people have 35mm projectors at home. If you have it on Blu-Ray or DVD, to see it on film is a way of dragging someone out from their house to come and see it at the cinema.”

Currently screening is Stanley Kubrick’s 1968 epic 2001: A Space Odyssey in 70mm. It’s an incredible presentation of what Vickery says is a seven or eight year-old print struck from the film’s original negatives: the colour of the picture is far richer, while the fine detail in some close-up shots is on par with modern movies. Even more impressive, though, is that the screening is packed. “Fifteen years ago, there would be cinemas where that would be almost on a circuit,” laments Vickery. “We've just stayed the course, and that's something that's just fallen away and we're one of the last, along with the BFI, to show films from film.

“There’s still a bit kicking around, but as we do more and more of it, we seem to be pulling out those people who are looking for that and they seem to be coming back again and again. The repertory side of our programme is more popular than ever.”

That popularity is seemingly reflected in its audiences’ passion for celluloid. Vickery tells me that the PCC’s suggestions board and social media are always filled with requests for film screenings, with specific questions about the way it’s being projected.

For Vickery, it’s a mark of pride. “It sounds like inflated ego almost,” he begins, as if providing a disclaimer, “but it's why I think the work we do and the BFI do and any cinema that shows films from film is about history. By us continuing to show film on film, studios will continue to make their film print available and keep them going out. If people stop showing films on film, they'd just get rid of them.

“Once they're all gone, the only way we're ever gonna be able to see them is if they're taking these films and digitising them, which as you imagine, is always going to be the classic set of films, and then there'll be very select ones will get picked, but it's not gonna be every film.

“You have to keep showing films from film to keep the history of cinema alive in cinemas.”

****

History is something that the BFI is committed to preserving. 40 per cent of their annual programming is projected on celluloid, and they loan around 200 prints to venues each year. Their new “BFI 2022” initiative will produce 100 new film prints in the next five years.

Most recently they have focussed on safeguarding their archive, the BFI’s creative director Heather Stewart tells me when we meet her in her office in the BFI’s artsy offices just off Tottenham Court Road.

“We got money from the government to renew our storage which was a big deal because the national collection really wasn't safe,” she says “There was work at risk because it was warm and humid and we have bought a fantastic, sub-zero state of the art storage facility in Warwickshire in our big site there and our negatives are there. So our master materials are all in there safe - all the nitrate negatives and all that. In 200 years, people will be able to come back and make materials from those, whether digitising or analogue.”

Stewart tells me that it’s important to do both: “Do we at the BFI think that audiences need to see films in the way the filmmaker intended? Yes. That's not going away - that's what we're here for. Do we want as many audiences as possible to see the film? Yes. So of course we're interested in digital.”

The restoration and printing project is attracting lots of “international interest” according to Stewart: just one example is that the BFI are looking into partnering with Warner Bros in their labs in Burbank, California.

“We're becoming the only place left that actually loans film prints around the world so that you can see the films the way they were intended,” she says. “So if you don't have any kind of renewal programme, you'll eventually just have blanked out, scratchy old prints and you can't see them."

They're getting financial support too, she says: “There are people like Christopher Nolan, Quentin Tarantino, Paul Thomas Anderson [director of Oscar-winner There Will Be Blood whose 2012 film The Master was shot and screened in 70mm], a lot of people who are very committed to film, and so there's conversations going on elsewhere and with the film foundation about bringing other investments in so we can really go for it and have a fantastic collection of great great 35mm prints for audiences to look at.”

As a fan of the film reel, Stewart is passionate about this. I put to her the common suggestion that lay audiences can’t tell the difference between screening on film, and digital. “I don't agree with that", she says. "If you sit with people and look at it, they feel something that you might not be able to articulate.

“It's the realism the film gives you - that organic thing, the light going through the film is not the same as the binary of 0s and 1s. It's a different sensation. Which isn't to say that digital is 'lesser than', but it's a different effect. People know. They feel it in their bodies, the excitement becomes more real. There's that pleasure of film, of course but I don't want to be too geeky about it.”

Yet not every film print available is in good condition. “There's a live discussion,” says Stewart. “Is it better to show a scratched 35mm print of some great film, or a really excellent digital transfer?”

There’s no neat answer.

But Stewart is certainly driven by the idea of presenting films as closely as possible to the filmmakers’ true vision. “If you're interested in the artwork,” she explains, “that's what the artwork has to look like, and digital will be an approximation of that. If you spend a lot of money, and I mean really a lot of money, it can be an excellent approximation of that. But lots of digital transfers are not great - they're cheap. They're fine, but they're never going to be like the original.”

The process of restoration doesn’t end with digitisation. Keeping film copies in order to have originals is hugely important given how quickly digital media change. Film is a constant form of storage which does not alter. As Stewart defiantly puts it, “all archives worldwide are on the same page and the plan is to continue looking after analogue, so it ain't going anywhere.”

****

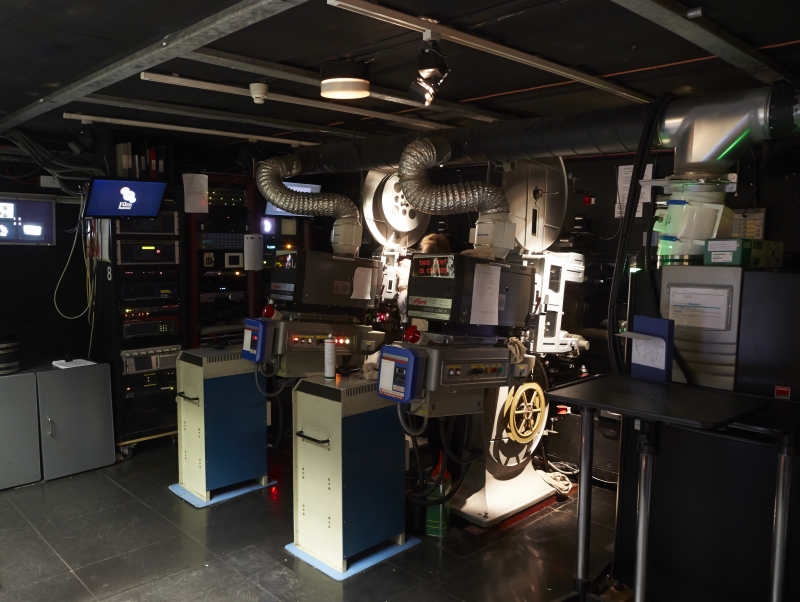

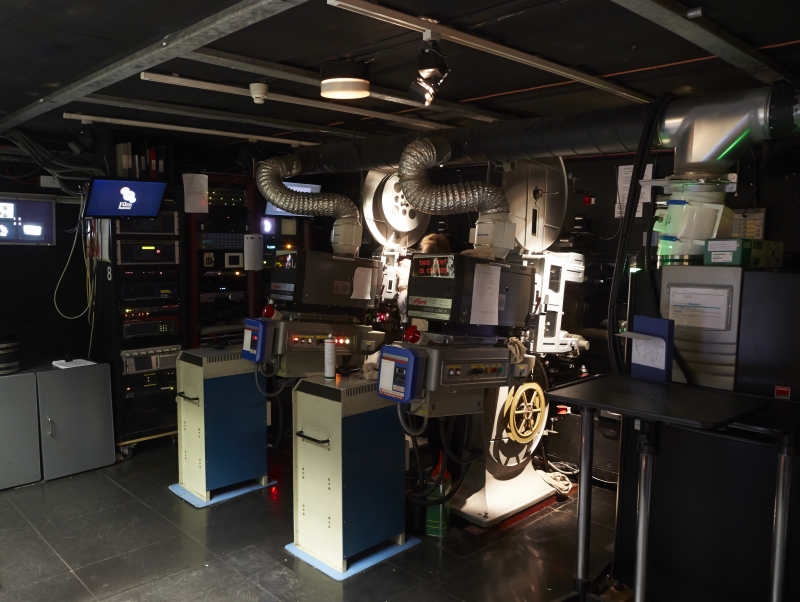

The BFI were kind enough put on a display of how film projection works in practice. Tina McFarling, Media Advisor, and Dominic Simmons, Head of Technical, provide a tour of two screens at BFI Southbank. Chatting in the projection room above the screen which hosted the 70mm première of Dunkirk, their passion for celluloid was on display.

Standing next to two mammoth 70mm projectors, Simmons talks through the real-terms use of film, and the technical expertise behind it. “It's a lot more labour intensive than sticking digital prints on, but it's something we want to do,” he says.

One of the projection booths at the BFI

During the visit, the team are prepping a rare 35mm screening of the documentary I Am Cuba to be shown that afternoon. Simmons says that operating a celluloid projector is a “more complex operation” than digital. Looking at the endless labyrinth of film and sprockets, it's easy to believe.

“If you're screening from film in a cinema,” he says, “then you need engineers, technicians who are capable of doing it, whereas a lot of multiplexes have deskilled their operation.”

Simmons says that, while larger chains have one engineer to oversee every screen with the actual process of running the films centralised with a centre loading playlists, the BFI has twenty-two technicians, each closely overseeing the projection of a film when on duty.

“There's so much about the different elements of the presentation that you need to know that all comes together with the sound, the lighting and the rest of it.

“When you're starting a film, it's more of a manual operation. Someone needs to be there to press the buttons at the right time, manage the sound, operate the curtains, and attach the trailers to the feature.”

Having skilled operators is all very well, but of course you need to have the equipment to operate in the first place. “We have to make sure that the equipment is kept and utilised as well as making sure the prints are available, and then the skills will follow”, he says.

Simmons says many are likening the film fight back to vinyl’s resurrection, but has a rueful smile when he talks about film being described as “hipsterish” and “boutiquey”.

He also points out that the quaint touches that make film attractive to this new, younger audience – blemishes, the occasional scratch – are a headache for projectionists. “For me,” he says, “that's quite difficult because a bad print of a film is never a good thing, but if it's a bad print of a film that can't be seen any other way...” He trails off sadly.

The threat of damage to film prints is constant, he says. “Every time you run a film print through a projector there is some element of damage done to it. You're running it over sprockets at loads of feet per second.”

He switches a nearby projector on – it’s loud, quick and, after leaning in to look more closely, it’s easy to see that it’s violent. “It's a really physical process,” Simmons continues. “The film is starting and stopping 24 times a second.”

The idea that shooting on film, for which the very raw material is in short and ever-decreasing supply, is endangered is a tragic one. “There's a finite amount,” Simmons says. “People aren't striking new prints, so if you damage a print, the damage is there forever.”

****

The Prince Charles and the BFI are in a privileged position to protect endangered film stock. A friendly partnership between them, which sees the BFI lending reels to the Prince Charles, as well as benefitting from the business of London’s rabidly cinephile audience, allow them to prioritise screening on film the majority of the time. Not every cinema is so lucky.

While the historic Ultimate Picture Palace in Oxford does have a 35mm projector, owner Becky Hallsmith says that it’s mainly the digital projector in use “for all sorts of logistic reasons”.

Though Dunkirk’s push for film projection was a welcome one, it still didn’t make sense for the UPP to screen it. “Certainly we thought about it, but I felt that if you're going to see it on celluloid, you probably want to see it on 70mm, so we decided not to get it on 35mm.”

Economic factors come into effect here too – the UPP, based just out of the city centre in Cowley, vies for Oxford’s filmgoers’ love with the Phoenix Picturehouse in nearby Jericho. While they do have slightly different markets, Hallsmith was aware that the Picturehouse was already set to screen Dunkirk in 35mm, leading her to decide not to.

“It's not like I'm saying we never do it” she clarifies. “But there are reasons I haven't this time.”

Hallsmith was also aware that not all of her projectionists are trained in screening film, saying that, by screening Dunkirk in digital, she was “taking that little headache out of the equation”.

For the UPP, practicality of this kind trumps sentiment, given the cinema’s small operation. “I'd love it if I had the time to work out what films had beautiful 35mm prints and programme accordingly,” she says, “but I just don't have the time to put that amount of thought into details of programming. We're tiny. I'm doing all sorts of different jobs around the cinema as well. The programming is by no means the least important - it's the most important part of the job - but there is a limit to how much one can do and how much research one can do.”

Despite the practical issues related to 35mm, Hallsmith is still glad to have the option available, saying that when the digital projector was installed in 2012, there was enough room for the installation to account for the 35mm one – and to revamp it.

Despite many 35mm projectors being sent to an unceremonious death in skips, some projectors that are replaced for digital successors are cannibalised for parts. Hallsmith was a beneficiary. “Most of the bits on our 35mm projector are quite new,” she explains, “because they had all this stuff that they were taking out of other cinemas, so they upgraded our 35mm for us because they had all the parts to do it with.”

But Hallsmith is grounded when I ask her if having both projectors in operation is important. “It's important for me,” she laughs. “One of my real pleasures in life is to sit at the back near the projection room and to hear the film going through the sprocket. It's one of the most magical sounds in the world and always will be for me.

“But I know that for a lot of our customers, it is neither here nor there, so I have mixed feelings about it. It's not like I think everything should be on 35mm. I love it, but I can see the practicalities.”

****

It is certainly practicality that’s governing cinema chains. Cineworld, Odeon and Vue have all seen huge expansions in recent years. Vue chief Tim Richards, says celluloid is a “niche product”, but the admission is tinged with sadness.

“The problem that we had,” he says about the 70mm screenings of Dunkirk, “with the conversion to digital that happened globally, there are literally no projectors left anywhere, and it's very, very hard to get one. We managed to find a projector and then we couldn't find anybody who actually knew how to run it. There are very real practical issues with the medium.

“To reinforce that we have a new look and feel to our head office, and I really wanted to have an old analogue 35mm projector in our reception and we couldn't find one. We had thousands of these things, and we had none left. We couldn't even get one for our reception!”

Even with a working projector and a trained projectionist, Richards says the format has “very obvious issues” with mass consumption. Again on the subject of Dunkirk, this time in 35mm, he says, “One of the prints that arrived was scratched. It's something that's been in the industry for a long time. If you have a big scratch, you simply can't screen it. You've got to get another print, especially when it will run through part of the film.”

It’s something that saddens Richards, who still says that projecting on film forms part of the “philosophy” of Vue. “We’re all big supporters [of film] and we love it. We've all been in the industry for between 25 and 30 years, the whole senior team. We genuinely love what we do, we genuinely love movies.”

That said, Richards, who is a governor of the BFI, is firmly committed to refining digital, more practical for Vue’s multiplexes. “If you go down and look at what we opened up in Leicester Square, our new flagship site, it's a 100 year old building where we shoehorned in new technology so it's not perfect, but it gives you an idea of what we're doing."

The new site has two Sony Finity 4K resolution projectors working in tandem – as well as the brand new Dolby Atmos sound system. The dual projection gives the screen a brighter, deeper hue. From a digital perspective, it is bleeding edge, and the set up is being rolled out across the UK and Germany, with 44 sites and counting. Richards is, as you would expect, enamoured with the results, claiming “that screen stands up to anything in the world”. What might be more surprising are the reactions he claims that it has elicited from celluloid devotees.

“There were a lot of old hardcore film fans there who were pleasantly surprised at the quality” he says. “People think of digital as being that new, TV-at-home which has got that clinical feel to it, and they don't feel it's got that warmth and colour saturation. This [Finity presentation] has that warmth of an old 35mm or 70mm, so I don't think the future is going back.”

****

For Richards and Vue, the future appears to be as bright as that 4K Sony Finity screen in Leicester Square - for celluloid, not so much. While the appetite for watching movies on film might be growing at a promising rate for indie exhibitors, the list of technical and logistical problems is still insurmountable for many smaller venues - saying nothing of the race against time to preserve easily-damaged prints.

The main concern is an ephemeral one: the preservation of the knowledge needed to run a film projection. When the BFI’s Dominic Simmons speaks about the skills of his team and the need to pass those skills on, it evokes near forgotten skills such as thatching and forging. If the BFI and the PCC have anything to say about it, those projection skills will live on, but it’s unclear how far their voices can carry in a digital multiplex age.

As for the voice of celluloid-lover-supreme Christopher Nolan, even he too is shouting down what seems to be an unstoppable march towards a convenient digital future. But in a groundswell of growing interest and passion for the film reel, it seems that a director so obsessed with playing with time in his films seems to have bought exactly that for celluloid. Time is running out on the film reel, but there might be more of it left than we thought.

| IP: Logged

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Mike Blakesley

Film God

Posts: 12767

From: Forsyth, Montana

Registered: Jun 99

|

posted 09-01-2017 08:03 PM

posted 09-01-2017 08:03 PM

quote: Alexandre Pereira

Really keys have nothing to do with payment?...So they have everything to do with avoiding piracy? As in piracy of piratebay where you cannot find any of the recent releases?

Try not paying on a seven day pay on a new release and then hold your breath for next week's key.

Same thing happened with film.... if you didn't pay, you didn't get the next movie from that studio. Or, in severe enough cases, they would send a guy to pick up the print from you. The keys are maybe 5% about payment and 95% about piracy or unauthorized shows.

quote: Alexandre Pereira

Speaking of fair - where was the gain for exhibitors in moving to digital?...Maybe in spending all that money on digital and subsequent upkeep and upgrade.

Hmm let's see...not having to deal with damaged film, access to all the trailers we ever need, shipping is less than 1/3 the cost of film, reduced projection booth wages, easy to move a movie from one auditorium to another, no backbreaking huge boxes or cans to carry up/down stairs, easy 3-D capability, improved sound, automation cues easier to set up, less maintenance, shows can be programmed in advance with no threading required, being able to tweak and adjust the trailer pack on the fly, being able to stop the movie easily if nobody shows up, being able to do really cool things for customers like show them the first 10 minutes of a movie they missed, old movies being available in "good" condition again, and so on. (I realize there are a few things on this list that only benefit a small operator like myself.)

| IP: Logged

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Victor Liorentas

Jedi Master Film Handler

Posts: 800

From: london ontario canada

Registered: May 2009

|

posted 09-01-2017 11:41 PM

posted 09-01-2017 11:41 PM

I understand only too well the attitudes of those who feel "good riddance"to film but I really do miss it. ![[Frown]](frown.gif) I truly loved being a reel projectionist but I also miss the beauty and magic of good film projection as a movie fan. I truly loved being a reel projectionist but I also miss the beauty and magic of good film projection as a movie fan.

The impact of the near overnight destruction of film and even the possibility that it could coexist along side digital has truly hurt me in so many ways. After a few years of it I can only now really take it all in.

My goal these days? Just to keep it alive where I can and enjoy the magic it still produces,given the chance.

http://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/films/features/dunkirk-film-digital-christopher-nolan-quentin-tarantino-paul-thomas-anderson-lawrence-of-arabia-a7918586.html

Film vs Digital? In the same way that a new generation of music lovers are rediscovering vinyl, cinema enthusiasts are discovering, or rediscovering, celluloid

Thanks to high-profile directors like Christopher Nolan, Quentin Tarantino and Paul Thomas Anderson, some titles are still shot and projected on film – but not that many

Geoffrey Macnab

@TheIndyFilm

Thursday 31 August 2017 08:45 BST

2 comments

293

Click to follow

The Independent Culture

chris-nolan.jpg

The director Christopher Nolan shot his recent wartime epic ‘Dunkirk’ on film, not digital Paramount Pictures

In the wake of Christopher Nolan’s wartime epic Dunkirk, which was released in July, the long-simmering debate about the respective merits of film and digital is again coming to the boil.

In interviews, Nolan has wasted no opportunity to proclaim the superiority of film over digital. He lets everyone know that Dunkirk was shot on film, much of it using IMAX cameras. Cinematographer Hoyte van Hoytema, strongly tipped for awards nominations for his work on the movie, likewise champions the benefits of old-fashioned film.

In the mad scramble to convert cinemas for digital projection, van Hoytema argues that the industry has been contributing to the “fast decline of a sublime technology a hundred years in the making”.

When we go to see a movie at our local cinema, he points out, it is likely to be projected with a 2K resolution

dunkirk-1.jpg

A scene from Nolan’s ‘Dunkirk’ which has rekindled the film vs. digital debate. Much of ‘Dunkirk’ was shot using IMAX cameras (Rex)

“To put things in perspective: nowadays standard TVs are sold with twice that resolution,” van Hoytema notes. By contrast, a Dunkirk analogue IMAX film print is projected with close to 18K resolution. In other words, the gulf in quality is huge.

“You will hear people saying that the layman doesn’t know the difference. Truth of the matter is that without pinpointing exactly why, they [spectators] actually do see the difference. And if not now, they will in a few years, as the keen eye of the cinemagoer evolves rapidly. Remember when we thought DVDs looked incredible?” the cinematographer asks. He talks of recently watching David Lean’s Ryan’s Daughter in a restored 70mm film print and realising that it was “far superior than the best thing that the digital industry is offering up today”.

The implication is clear. Throwing out the cans of celluloid, closing the film labs and jettisoning the projectors has been nothing less than an act of cultural vandalism. Audiences have been hoodwinked into accepting films projected digitally that don’t have anything like the richness or resolution of old 35mm or 70mm prints.

Of course, the debate isn’t that simple at all. To those who remember films catching fire in the projector or watching scratchy old prints of supposedly new movies, digital projection has been a boon. It offers consistently, clarity, a clean image. It is cheaper and easier to shoot on digital too.

quentin-tarantino-1.jpg

Quentin Tarantino says he would give up directing if he couldn’t shoot on film (Rex)

Thanks to high-profile directors like Nolan, Quentin Tarantino and Paul Thomas Anderson, some titles are still shot and projected on film – but not that many. “If I can’t shoot on film, I’ll stop making movies,” Tarantino recently proclaimed but there is little sign yet that the public shares his enduring passion for photochemical film. Spectators aren’t picketing cinemas or demanding that film projectors be reinstalled. The film vs digital debate itself has been running for years and even inspired a movie of its own, Side By Side (2012), produced by Keanu Reeves. This feature documentary, featuring Nolan, James Cameron, Martin Scorsese, George Lucas and others, appeared to rehearse every side of the argument at exhaustive length. Nonetheless, five years later, the debate is still rumbling on.

“For me, the means by which the film is being presented to the public is less important than the story that is being told,” says Nick Varley, co-ceo of Park Circus, a company that has been highly successful in re-releasing back catalogue classics into cinemas, most of them in digitally restored versions. As Varley points out, if it’s a lousy film, the format on which it is shown becomes irrelevant anyway.

Scorsese is one of the great champions of film but when he was interviewed at the BFI earlier this summer, he spoke very movingly and evocatively about the circumstances in which he first saw many of his favourite movies… crouched down in front of the battered old family TV.

No one denies the magic of holding film or of feeding it through a projector. There’s little such romance with digital. (You can’t hold an electronic file in your hands.) Nonetheless, the digital revolution has made many more classic movies available than ever before. “What digital cinema and digital distribution has allowed us to do, certainly in our business, is to take films and restore them so they look as good as the director intended them to,” he says.

lawrence-of-arabia.jpg

‘Lawrence Of Arabia’ is being re-released on a new 70mm print and screened at the BFI in September – special screenings like this always sell out (Rex)

The advantages of digital distribution are also self-evident. The same film can be shown at the same time in a cinema in London and one in Orkney. There’s no need to pay expensive transport costs for film prints. Everyone knows, too, that celluloid deteriorates. However careful the projectionist is in handling a movie, by the time it has been projected 20 or 30 times, there will be specks of dust and scratches. The digital version, though, should remain unblemished.

Park Circus is partnering with the Prince Charles Cinema in London on Check The Gate, a season of 35mm films, from 22-24 September. The programme includes such titles as Boogie Nights, Jackie Brown and Taxi Driver. Prints for the films aren’t all in pristine condition but audiences don’t mind. In the same way that a new generation of music lovers are rediscovering vinyl, cinema enthusiasts are discovering, or rediscovering, celluloid.

How to End an Email: 9 Never-Fail Sign-Offs and 9 to…Get Grammarly. It's free!

These Crossovers Are The Cream Of The Crop!Yahoo Search

17 Brides You Can't UnseeSemesterz

by Taboola

Sponsored Links

“If you remove the ability to play 35mm prints, you instantly lose a large part of cinema history,” says Paul Vickery, head programmer of The Prince Charles Cinema.

Park Circus represents over 25,000 films from Hollywood and British studios. The company still maintains several thousand 35mm prints. This is a matter of practicality as much as it is a nod to film history; huge numbers of classic old movies still haven’t been digitised, they’re only available on film.

Special 70mm screenings of popular titles like 2001: A Space Odyssey and Lawrence Of Arabia still sell out. It costs around £25,000 to strike a single new 70mm print of such a title, as opposed to $100 for a Digital Cinema Package (DCP) of the same film. Nonetheless, the box office justifies the extra expense. One of the ironies is that these old classics will be restored digitally even if they are then projected on film. Nonetheless, film has a mystique that digital just can’t match and seeing 2001 projected in a cinema is still an event.

boogie-nights.jpg

Julianne Moore and Mark Wahlberg in ‘Boogie Nights’, which will be screened later this month as part of a season of 35mm films at London’s Prince Charles Cinema (Rex)

“There is grain on film that’s not present on digital,” Vickery explains the enduring aesthetic and organic appeal of projected film. “[With] a moving film print, every film has a different make-up of grains. It looks like every image is moving within itself because of the grain whereas the digital version is very flat. There is nothing happening beyond the hard lines of the object you’re looking at.”

The good news for “film” lovers is that the format isn’t disappearing. Seasons like Check The Gate and revivals of Lawrence Of Arabia on 70mm suggest that digital hasn’t squeezed film entirely out of existence quite yet. Hollywood is bound to notice the hugely enthusiastic response to Dunkirk. At the world’s leading archives, even movies shot originally on digital are still preserved on film. Prominent directors and cinematographers continue to proselytise on behalf of film. “I think as filmmakers we can’t allow that medium [film] to disappear from our palette,” says van Hoytema. “It’s far too good and far too beautiful, and there is no valid replacement yet, or perhaps never will be.”

Nonetheless, there is no turning back. Film still has its place for historians and cinephiles but it’s no longer in the mainstream. The success of Dunkirk won’t stem the retreat or dent the dominance of digital in the long run.

The Prince Charles Cinema and Park Circus present Check the Gate, a season dedicated to presenting films on film, from 22-24 September; ‘Lawrence Of Arabia’ will be re-released on a new 70mm print, from 22 September to 3 October, at the BFI Southbank

| IP: Logged

|

|

Dave Bird

Jedi Master Film Handler

Posts: 777

From: Perth, Ontario, Canada

Registered: Jun 2000

|

posted 09-02-2017 08:40 AM

posted 09-02-2017 08:40 AM

I tell folks that I believe that film cameras/projectors (and/or the sewing machine) was probably the most reliable, best engineered system ever. Ran reliably for over a century, and still does really. I know our XL here in the booth still purrs like a kitten, but can't touch the brightness on a 72 foot screen outdoors that the Barco does.

As for the perception of "evil" or "greedy" (public) corporations, I guess I just never saw who it was exactly that referred to. As they are owned by millions of shareholders (directly or via pension or government holdings), benefitting rich, poor, workers, retired, Lib, Con, Dem, Republican, whoever....and bound by law specifically to grow or distribute shareholder value....why people expect them not to operate in this manner.

| IP: Logged

|

|

Jack Ondracek

Film God

Posts: 2348

From: Port Orchard, WA, USA

Registered: Oct 2002

|

posted 09-02-2017 11:44 AM

posted 09-02-2017 11:44 AM

The studios do own the content, not you or me. Whatever they do to control access to it is their prerogative. We have nothing to say about that. Think not? Give Disney a call and try some of this rationale on them.

The studios did pay for some of our projectors, in the form of VPF payments. That was fine, for those of us who were OK with the attached strings. For those who weren't, we were welcome to buy outright, and some of us did.

I spent 50 years in the booth. Don't remind me about the "romance of film". In its time and place, I was as big a cheerleader for film as anyone else. At the time we converted, I had 5 year-old Schneider lenses, 3 - 5 year-old Big Sky lamphouses, rock-steady projectors and freshly-painted screens. I'm not sure you could get a better image on an 86-foot screen or force any more energy through 35mm without incinerating it.

For 27 years, I sat in the booth and watched the wheels spin. Being ready for anything that might shut down a show was my job.

Today, I push "play". Many indoor houses don't even have to do that. My job as projectionist has vaporized. Now, I walk around, act like I own the place and watch how well my wife and I have turned the basic operations over to my daughter and staff.

My sound is better, my picture is much better, and my customers have noticed. I've had a few glitches with the technology, so I'd have to say it's about the same as when I had film... the incidences being not better or worse, but certainly different.

As for keys, payment, piracy, & the like... I'm not sure I buy any of it. So long as China and the torrent sites have the same content as I, but 3 days earlier, the studios still have a challenge on their hands, and that has little to do with me.

Film is no longer a practical option for my business, but I'd certainly come and watch it at yours.

| IP: Logged

|

|

Leo Enticknap

Film God

Posts: 7474

From: Loma Linda, CA

Registered: Jul 2000

|

posted 09-02-2017 01:54 PM

posted 09-02-2017 01:54 PM

The film worship feature articles that have been discussed on this site (and most of the ones that weren't) all have some characteristics in common.

1 - They are published in magazines, journals or websites written by and for upper middle class, upper middle income, above average educated cultural elitists.

2 - The interviewees are almost all academics, critics, workers in the top 5% (by income) of the nonprofit archives, museums, cinematheques, etc: people you will almost never find living in a flyover state (or outside the M25, if they're in Britain), or with personal circumstances that do not allow them to attend lavishly equipped arthouse/repertory theaters on a weekly basis.

3 - The writers and interviewees have a tendency to jump on whatever bandwagon is rolling past. Rewind 10-15 years, and the British Film Institute (also under Heather Stewart's effective leadership) was promoting and playing up its "Digital Screen Network" for all it was worth, and celebrating the DCP as something that would "free independent cinema from the tyranny of 35mm" (that's a direct quote, the ignorance of which seared into my memory at the time I read it). What it actually freed cinema from was the elitism that these people depend on to make their living, which is why Stewart and her ilk have done a 180 and are now spearheading the "bring back film" movement, their weapon of choice being cliche-laden quotes and press releases dished out to any liberal culture/arts publication that is willing to print them.

I used to work in the academic/archival world (between 2001-13), and the hypocritical opportunism on display in this article is a textbook example of why it'll be snowing in Hell before I ever do so again.

Nowhere in the article does it mention the fact that a suburban multiplex in the Midwest, or a three-screen indie in a non-university town can now play the occasional classic or arthouse title at all, whereas previously the economic and technical barriers to this happening were too high. Nowhere does this article mention that the digital remastering (and in some cases, restoration) processes that precede a rerelease DCP can also yield home viewing versions (DVD/BD/streaming) that people who can't get to a theatre at all can now see, whereas a generation ago they'd have been stuck with VHS or whatever was on offer from broadcasters.

None of this is to argue that those few venues that can still play film should not continue to do so for as long as they can. I would have loved to have seen Dunkirk and Wonder Woman in 5/70, but work and childcare commitments prevented me from doing so. Like around 98% of the theatrical audience for these movies, I saw the DCPs, and still enjoyed them. All of us here know that judged by the criterion of "bang for limited buck," (as distinct from bang for a blank check) a digital installation will outperform a 35mm one for image and audio quality in almost all real-world environments. But living in the real world is not something that the writers and interviewees in this article tend to do (hence Heather Stewart's "We got money from the government," as distinct from "from the taxpayer"), and so it has to be read through that filter.

| IP: Logged

|

|

|

|

Jack Ondracek

Film God

Posts: 2348

From: Port Orchard, WA, USA

Registered: Oct 2002

|

posted 09-02-2017 07:22 PM

posted 09-02-2017 07:22 PM

That's true, Justin. But this new technology allows the studios to take things much closer to the edge.

In the film days, if you had a depot near you, a print could be held up for COD at will-call. Give them the money and they gave you the print. After the depots consolidated and everything went out UPS, those on COD status had to have a payment cleared before a print went out the door. For many, that meant Tuesday or Wednesday. Today, a studio could hold keys right up until showtime, if they wanted to.

I'm sure you know all of this... I just don't see where there's much difference. It's like everything else these days. Internet, telephone, cell phone and satellite TV are all services that can be held up for payment, and turned back on just as soon as they get it.

Alexandre's objections to digitalization only seem to make sense if there's a deeper reason for it. There's nothing wrong with the studios protecting their property, to the extent they can. Now, if one might be objecting because of the notion that the consumption of intangible content over the air or internet should be free, and digital encryption gets in the way of that, well, that's something else altogether. It's also nothing new. People squawked when C-band Digicypher came out.

| IP: Logged

|

|

|

|

All times are Central (GMT -6:00)

|

This topic comprises 3 pages: 1 2 3

|

Powered by Infopop Corporation

UBB.classicTM

6.3.1.2

The Film-Tech Forums are designed for various members related to the cinema industry to express their opinions, viewpoints and testimonials on various products, services and events based upon speculation, personal knowledge and factual information through use, therefore all views represented here allow no liability upon the publishers of this web site and the owners of said views assume no liability for any ill will resulting from these postings. The posts made here are for educational as well as entertainment purposes and as such anyone viewing this portion of the website must accept these views as statements of the author of that opinion

and agrees to release the authors from any and all liability.

|

Home

Home

Products

Products

Store

Store

Forum

Forum

Warehouse

Warehouse

Contact Us

Contact Us

Printer-friendly view of this topic

Printer-friendly view of this topic

![[Frown]](frown.gif) I truly loved being a reel projectionist but I also miss the beauty and magic of good film projection as a movie fan.

I truly loved being a reel projectionist but I also miss the beauty and magic of good film projection as a movie fan.